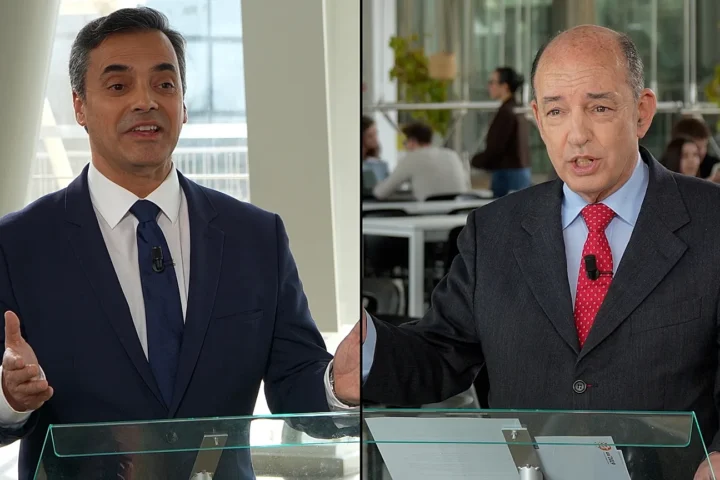

The debate over how the European Union should finance Ukraine’s defense and reconstruction has entered a decisive new phase after a forceful intervention by Valdis Dombrovskis, the European Commissioner for Economy and Productivity. Speaking on Euronews’ morning program Europe Today, Dombrovskis argued that the EU must end its prolonged internal discussions and move directly toward using frozen Russian assets to support Kyiv. His remarks represent one of the clearest signals yet that Brussels may be preparing to adopt a more assertive and historically unprecedented approach to wartime financing.

Since Russia launched its full-scale invasion in February 2022, the EU and its G7 partners have frozen hundreds of billions of euros in Russian sovereign and private assets. These funds, spread across European financial institutions and global clearing systems, were initially immobilized as part of a sanctions regime aimed at undermining the Kremlin’s ability to wage war. Yet despite their size and symbolic significance, these assets have remained largely untouched, with EU policymakers divided over whether they can be legally seized or should simply be held until peace negotiations begin. To date, only the profits generated from these assets—estimated at a few billion euros annually—have been allocated to Ukraine.

Dombrovskis’s intervention seeks to shift this cautious stance dramatically. In his interview, he stressed that Ukraine’s needs are immediate and urgent. Kyiv faces a severe budget deficit, persistent attacks on critical infrastructure, and a long-term reconstruction task that could exceed one trillion euros. The Commissioner argued that the EU cannot continue relying on incremental funding packages that require months of negotiation and unanimous member-state approval. Nor, he added, should European taxpayers be asked to shoulder the entire financial burden of a war that Russia itself initiated. Using Russia’s frozen assets, he insisted, is not only strategically sound but morally justified.

His remarks reflect growing frustration within the European Commission and among several member states that the bloc has allowed legal and political caution to overshadow strategic necessity. Lawyers and diplomats have long debated whether seizing sovereign Russian assets would violate international law, particularly doctrines concerning state immunity. Some governments fear such a move could trigger retaliatory seizures of Western property in Russia or undermine global confidence in European financial markets. Yet others argue that Russia’s actions in Ukraine constitute such a grave breach of international norms that the legal landscape has fundamentally changed, creating grounds for extraordinary measures.

Dombrovskis’s comments carry significant weight because of his portfolio. As the Commissioner responsible for the EU’s economic governance and productivity strategy, he is at the center of decisions on sanctions, financial flows, and economic resilience. His public endorsement of asset seizure suggests that the debate may soon move from theoretical discussion to concrete policy planning. Behind the scenes, officials have reportedly been studying various legal models—from reparations precedents to trust structures—to channel the assets into Ukraine’s reconstruction without violating foundational principles of property rights or financial stability.

The geopolitical backdrop makes this shift even more consequential. Ukraine’s Western allies are reassessing their long-term commitments amid political gridlock in Washington, elections across Europe, and war fatigue among some constituencies. Meanwhile, Russia has intensified its missile strikes, expanded weapons production, and sought to exploit any signs of hesitation in the West. For EU policymakers, the decision to tap frozen Russian assets is increasingly seen not only as an economic measure but as a strategic signal of resolve—one that demonstrates that Europe is prepared to sustain Ukraine’s defense regardless of political headwinds elsewhere.

If implemented, the use of frozen assets would mark a watershed moment in the EU’s foreign and economic policy, setting a precedent for how democracies respond to aggression in the 21st century. It would also raise the stakes with Moscow, which has warned that any seizure of its assets would be met with retaliatory measures. Yet the argument gaining traction in Brussels is that allowing Russia to wage a war without bearing financial consequences poses a far greater long-term risk than potential countermeasures.

Despite the urgency conveyed by Dombrovskis, major questions remain. Member states such as Germany, France, and Italy have historically taken a more cautious position, preferring to restrict the EU’s actions to the use of asset-generated profits rather than the underlying funds. The unanimity required for EU financial decisions means that even a handful of hesitant governments could delay or water down any proposal. Still, the political landscape is shifting, and what once seemed legally or politically impossible is becoming part of mainstream debate.

What is now clear is that the frozen-assets question can no longer be dismissed as an abstract legal puzzle. It has become central to Europe’s strategic posture, its credibility as a supporter of Ukraine, and its role in shaping the post-war order. Dombrovskis’s appeal effectively forces a choice: either the EU embraces a bold new financial instrument that compels Russia to shoulder part of the burden for its own aggression, or it risks appearing indecisive at a moment when Ukraine’s survival depends on consistent and substantial support.

As the war enters a more grinding and uncertain phase, Europe’s decisions over the coming months will help determine not only Ukraine’s fate but the future contours of international law, sanctions policy, and financial sovereignty. Dombrovskis has made clear where he believes the EU must stand. Whether the rest of the bloc follows is now one of the most consequential questions facing European leaders.